Circulation

Circulation management is based on the PTC manual handbook, where the third priority is to establish good circulation. Haemorrhage is responsible for about one third of in-hospital deaths due to trauma and is an important contributory factor for other causes of death, particularly head injury and multi organ failure. The global mortality burden from haemorrhage is stark, with an estimated 1.9 million deaths annually, most of which (1.5 million) can be attributed to physical trauma and .[1]

Principles

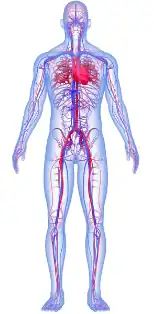

Basic Anatomy

Physiology

Shock

'Shock' is defined as inadequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation. Shock is a clinical diagnosis and it is most important to identify the cause. In the trauma patient shock is most often due to haemorrhage and hypovolaemia. The diagnosis and treatment of shock should occur almost simultaneously.

The diagnosis of shock is based on assessment of the clinical findings of:

- Tachycardia

- Decreased capillary refill time

- Hypotension

- Tachypnoea

- Decreased urine output

- Changes in mental state.

General observations such as pallor, hypothermia and cool extremities help to make the diagnosis. Physiological compensation for blood loss may prevent a measurable fall in blood pressure until up to 30% of the circulating volume has been lost. (See Appendix 5: Vital signs and Blood Loss.)

Classification

in a trauma patient is classified as haemorrhagic or non haemorrhagic.

Haemorrhagic shock:

is due to acute loss of blood and nearly all patients with multiple injuries have some hypovolaemia due to haemorrhage. The amount of blood loss after trauma is often poorly assessed and in blunt trauma is usually greatly underestimated. Large volumes of blood may be hidden in the chest, abdomen and pelvis or in the retroperitoneal space.

The treatment principles in haemorrhagic shock are to stop the bleeding and replace the blood loss.

Non haemorrhagic shock

includes cardiogenic shock, (myocardial dysfunction, cardiac tamponade and tension pneumothorax), neurogenic shock, burns and septic shock.

- Cardiogenic shock is due to inadequate heart function. This may be from

- Myocardial contusion

- Cardiac tamponade from both blunt and penetrating injury

- Tension pneumothorax (preventing blood returning to heart)

- Myocardial infarction

Clinical assessment of the jugular venous pressure is important in cardiogenic shock. It is often increased. Continuous ECG monitoring and central venous pressure (CVP) measurement can be useful as can the use of diagnostic ultrasound.

Neurogenic shock is due to the loss of sympathetic tone, usually resulting from spinal cord injury. Isolated intracranial injuries do not cause shock. The features of neurogenic shock are hypotension without compensatory tachycardia or skin vasoconstriction. Hypotension in patients with spinal cord injury can often also be due to bleeding.

Septic shock is rare in the early phase of trauma but is a common cause of late death via multi-organ failure in the weeks following injury. Septic shock may occur with penetrating abdominal injury and contamination of the peritoneal cavity by intestinal contents. If the patient does not have a fever it may be difficult to distinguish from haemorrhagic shock.

Most non haemorrhagic shock responds to fluid resuscitation, although the response is partial and or short lasting. Therefore if the clinical signs of shock are present, treatment is started as if the patient has haemorrhagic shock while the cause of the shock is identified.

The most common cause of shock in trauma is haemorrhage.

Haemorrhage, Hypovolaemia and Resuscitation

It is important to stop the bleeding but this may not always be straightforward especially if the source of haemorrhage is within the chest, abdomen or pelvis. The goal is to restore blood and oxygen flow to the vital organs by the administration of fluid and blood to replace the intravascular volume lost.

Management

- Insert at least two large-bore IV cannulas (16 gauge or larger). Jugular, femoral or subclavian venous access, cut down or intraosseous infusions may be necessary.

- Take blood for type, cross match and laboratory tests.

- First line infusion fluids are crystalloid electrolyte solutions e.g. Ringers Lactate (Hartmann's solution) or Normal Saline. Blood loss of more than 10% of blood volume (7 ml/kg in adults) or continuing expected blood loss will require blood transfusion (See Appendix 6).

- All fluids must be warmed to body temperature if possible. Hypothermia prevents clotting.

- Do not give IV solutions containing glucose.

- The routine use of vasoconstrictors is not recommended.

The exact amount of fluid and blood required is very difficult to estimate and is evaluated by the response of blood pressure and pulse to the resuscitation fluids. An initial fast bolus of 250ml is recommended in adults, followed by re-assessment. If there is no change in the vital signs, this bolus is repeated as necessary and ongoing haemorrhage must be excluded. The aim is to restore the blood pressure and pulse toward normal values.

Hypotensive resuscitation (to a mean BP of 70mmHg) may be used for penetrating trauma and also for severe pelvic fractures where the bleeding cannot be stopped without surgery, but hypotension is potentially harmful in patients with significant head injuries. (See also Appendix 6)

Urine output is an important sign of adequate resuscitation and renal perfusion. Urine output should be more than 0.5 ml/kg/hr in adults and 1 ml/kg/hr in children.

Unconscious patients may need a urinary catheter.

In remote locations where IV Fluids are unavailable and long distance patient transfer is necessary oral fluids might be useful. If many hours have elapsed since the injury, the patient may also need to "catch up" on maintenance fluids - 125 ml per hour elapsed.

The improvement of the blood pressure, pulse and general observations (colour, perfusion, mental status) in response to the resuscitation fluids is evidence that the loss of circulating volume is being corrected.

Blood Transfusion

See also appendix 6: Massive Transfusion)

Blood transfusion must be considered if a patient has persistent hypotension and tachycardia despite receiving adequate/large volumes of resuscitation crystalloid fluids. Transfusion may also be necessary if there is on-going haemorrhage and/or the haemoglobin level is less than 7 g/dl.

Blood may be difficult to obtain and blood products such as fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelets may be unavailable. In this situation, fresh whole blood from "walking" donors or relatives is best.

If type specific or fully cross-matched blood is not available, O negative packed red blood cells should be used in patients who are at risk of life-threatening bleeding.

Tranexamic acid, if available, can reduce bleeding and risk of death. It should be used early in resuscitation, with a loading dose of 1 gram over 10 minutes and then an infusion of 1 gram over 8 hours.

Sites of Haemorrhage

The priority is to identify the sites of haemorrhage and stop the bleeding.

In external bleeding sites, direct pressure is the most useful method to stop haemorrhage.

Injuries to the limbs

Tourniquets may be used if there is life threatening bleeding and direct pressure or a pressure dressing fails to control haemorrhage. Pre-hospital tourniquets save lives in military trauma, especially if applied before the onset of shock. It is important to note the time of tourniquet application. Complications can occur as a result of tourniquets.

Injuries to the chest

Sources of bleeding include aortic rupture, myocardial rupture and injuries to the pulmonary vessels. Other sources of haemorrhage are chest wall injuries involving intercostal or mammary blood vessels. Insertion of a chest tube allows the measurement of blood loss, re-expansion of the lung and tamponade of the bleeding source.

Injuries to the Abdomen and Pelvis

A laparotomy should be done as soon as possible in patients where there is a clinical indication that the bleeding is within the abdomen and fluid resuscitation cannot maintain a systolic BP at 80-90 mm Hg.

The sole objective of a damage control laparotomy is to stop immediate life threatening bleeding with sutures and packs. After resuscitation and stabilization a "second look" laparotomy is performed with definitive surgical procedures.

Pelvic fractures should be reduced by the application of a pelvic sling, which may help to control bleeding.

References

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095-128.

| Authors | William M Nabulyato |

|---|---|

| License | CC-BY-SA-4.0 |

| Cite as | William M Nabulyato (2022–2025). "PTC Course/Circulation". Appropedia. Retrieved November 28, 2025. |